With the protests in Turkey seeming set to continue despite Sunday’s clearing of Gezi Park (major trade unions have called for a strike on Monday), let’s look at a trend that a new friend (a Turkish national) pointed out a few days back.

One fascinating aspect of the protests has been the high level of social media sophistication supporting them, something my friend attributes in part to the presence of a robust community of communications professionals in Istanbul.

For a glimpse at what he was talking about, check out the “Diren Gezi Parki” Facebook page, which popped up early in the protests and picked up hundreds of thousands of followers within days. Note the careful preparation of content, with photo-focused news updates, which take advantage of Facebook’s love of visual content, translated into English for the international press.

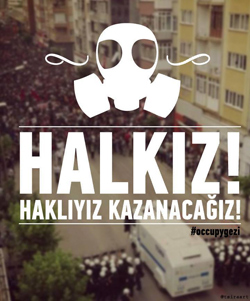

In general, the page imagery is excellent — the posters page is particularly striking (from the Facebook page, go to ‘Photos/Albums/Posterlerle Gezi Parki Direnisi’ if the direct link doesn’t work), with the bulk of the dozens of posters showing the clear influence of a designer’s hand. Also note the protesters’ appropriation of tear gas and the Erdogan’s slur against them (“looters”) as their own emblems). Note: check out the end of the article for another striking example.

As of this writing, the page has 612,748 likes and 707,876 “talking about this,” a powerful indicator of its ability to inspire public discussion.

Also noteworthy: an Indiegogo campaign to crowdfund a full-page ad in the NY Times, a great example ability of online tools to intervene in the real world. The ad itself caught an influential audience, but its funding mechanism in itself also drew plenty of coverage.

Of course, Facebook’s not exactly the right medium if you’re trying to keep your plans out of the hands of the authorities, but according to an article in The Telegraph (note: whose name itself preserves a much older age of rapidly changing communications technology), the actual organizing work is happening on private digital channels:

[Damla] will receive links to maps only visible to fellow activists that show the location of makeshift clinics in houses and even in restaurants’ basements…

Damla said the use of private group messaging meant activists could “react quickly to check whether we’re all safe”, and added that if access to Facebook and Twitter was temporarily disrupted, as it has been on each day of the protests, they would merely start communicating through the blogging site Tumblr instead.

Protesters became more careful about communicating information privately after they realised police knew where they were, tracking public posts on social media. “We were giving out information to police without realising,” Damla said.

After that, links and groups visible only to each other became the way they communicated their location or movements, though they were happy to denounce Erdogan’s government and upload photos of alleged police brutality on Twitter or Tumblr.

Exactly the right approach: use the public side of Facebook and Twitter for what they’re good at (public communications) and turn to invite-only channels for the real work of getting people out on the streets. That way, when the police come after your Twitter activists, others can keep working behind the scenes. In that vein, lso note The Telegraph article’s mention of anonymity-preserving technology at work, crucial for keeping the cops out of your inbox.

With all their social media and online tech savvy, I bet the Turkish protesters are still keeping a close watch out for undercover police and intelligence officers, though, since a hidden network is only as safe as its most trustworthy member. From cuneiform to microdots to encrypted wifi, even the best technology is vulnerable to “human engineering” — the old rules evolve, but they rarely change completely. Welcome to the modern world.

– cpd