Yesterday’s hacking of a U.S. military Twitter feed and YouTube page may not be militarily significant in any material way, but it IS a classic act of war…of the psychological variety.

The hackers (presumably associated with the “Islamic State” in Syria and Iraq) didn’t do any substantive damage when they cracked open a couple of Central Command social media accounts. As P.W. Singer notes on Wired.com, “No critical command and control networks were touched, nor, for that matter, were any of the military’s internal or external computer networks that are used to move classified or even run-of-the-mill information.” Was the attack a meaningless act of vandalism, as the title of Singer’s piece (“It Doesn’t Really Matter if ISIS Sympathizers Hacked Central Command’s Twitter”) implies?

But the REAL target of the hack wasn’t a U.S. Central Command social media feed: it was the hearts and minds of potential Islamic State supporters around the world, making the attack a textbook piece of psychological warfare. As the name implies, psychological warfare goes after people’s feelings and thoughts, and intentional psychological warfare is as old as war itself, dating perhaps to the first time a paleolithic hunter/gatherer donned the skin of a lion to frighten a rival group out of a fight for territory or food.

In the case of ISIS or its sympathizers, the Twitter hack likely wasn’t designed as much to scare as to impress, to demonstrate to potential supporters that the organization is powerful enough to humble the mighty United States military. Social media’s public nature makes Twitter or YouTube a perfect venue for such a propaganda victory, even if the attackers caused no material damage and advanced the front lines in Iraq not one foot.

At this moment, as Terrence McCoy points out in the Post, the Islamic State NEEDS some kind of public victory, because they’re stalled on the battlefield and failing as an organized government in the areas they control. The result? Low morale, which translates into even worse battlefield performance and lower recruiting. In this context, a public demonstration of their effectiveness becomes as important as a substantive achievement in the field. This quote from McCoy’s piece nails the intent:

“What we’ve seen is the transformation of a low strategic target into a high value target,” said Levy-Yurista of the technology security outfit Usher. “….By humiliating us they throw a message out there that will help them gain resources in terms of recruits.”

Of course, you can’t beat the U.S. Army with a Twitter attack, annoying or embarrassing as it is. But an act that’s in itself militarily meaningless can still have military consequences, depending on how it’s perceived. One classic example: the “Doolittle Raid” in April, 1942, launched after the Japanese had crushed the U.S. battle fleet at Pearl Harbor, taken our mid-Pacific Islands and were in the process of kicking the Western powers out of what’s now Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines.

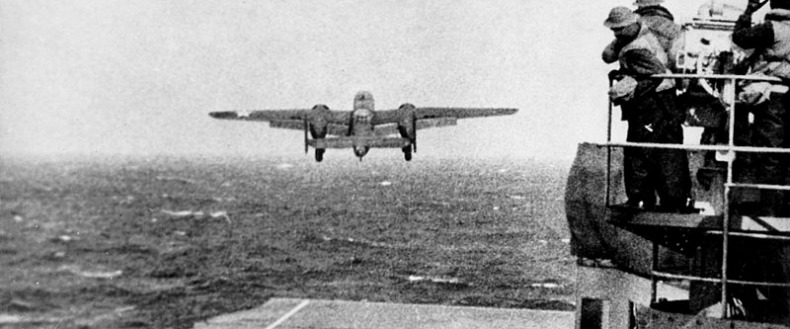

But that spring, the U.S. Army Air Corps and Navy combined for a psychological coup. By launching sixteen twin-engined Army bombers from the aircraft carrier Hornet, they managed to bomb targets in Tokyo and several other Japanese cities, something that the Japanese leadership assumed could not happen. All the planes were lost (crash-landed in China or interned in Russia), and the raid did essentially no military damage, but it boosted American public morale when the country needed it. Most importantly, the attack convinced the Japanese high command that they had to destroy America’s remaining aircraft carriers…leading directly to the Battle of Midway, a strategic disaster for the Japanese and a true turning point in World War II.

The Doolittle raid was a stunt…but it was a stunt with consequences. Psychological warfare works when it works: if it invigorates your supporters, demoralizes your opponents or forces them into an error, its effects can extend far beyond any immediate damage. In the case of ISIS and Twitter, imagine a retaliatory attack on a hacker cell that ends up killing civilians in large numbers by accident, creating international pressure against the U.S. bombing campaign against the Islamic State. At the least, this hack may draw desperately needed foot soldiers toward the group, particularly ones from the West who can then be recycled back into their home countries for Charlie Hebdo-style attacks.

The internet creates a wholly new venue for psychological warfare, and the U.S. and other governments have long worried about the ability of extremist groups to leverage digital tools to reach audiences far from their home bases. With this attack, meaningless as it is in objective terms, the Islamic State (or its sympathizers) have demonstrated their ability to interfere with the U.S. military in a public technological venue — defeating America on its home ground, as it were. Whether or not they can capitalize on this burst of publicity is another story, one still unfolding before our eyes. Let’s hope it fizzles rather than burns.

– cpd

Image: B-25 leaves the deck of the Hornet, bound for Tokyo. Photo courtesy Wikipedia.